A record

of concern:

The Anderson birth was hardly the first time that

Community Hospitals officials had cause to doubt Morgan's

care.

In 1986, Community put Morgan on a year's probation and

ordered a review of his obstetrical and gynecological

cases after he refused to respond to nurses' complaints

about "medical management of specific cases."

In addition, hospital records show, concern was expressed

about Morgan's "adherence to guidelines and policies"

of the obstetrics and gynecology department. Also

questioned was the physician's manner of communicating

with the nursing staff.

Further, from 1988 to 1990, Morgan had "significant

quality of care issues."

Morgan, in his state deposition, confirmed that Community

Hospitals officials long were uncomfortable with his

medical approach.

He complained that they had scrutinized him since the

1980s.

"They had a magnifying glass out," he said.

Morgan's patients, though, would never know it.

All the hospitals' review proceedings were, as the law

provides, held in private.

Publicly, Community presented Morgan as a doctor in good

standing.

In March 1990 - less than two months after Kyle

Anderson's death - Community included Morgan's name among

hundreds of staff physicians in a newspaper advertisement

marking National Doctors Day.

The headline: "How to recognize a good physician

when you see one."

Three months later, The Indianapolis Star published a

Pulitzer Prize-winning series exposing flaws in the

state's system for disciplining negligent doctors. The

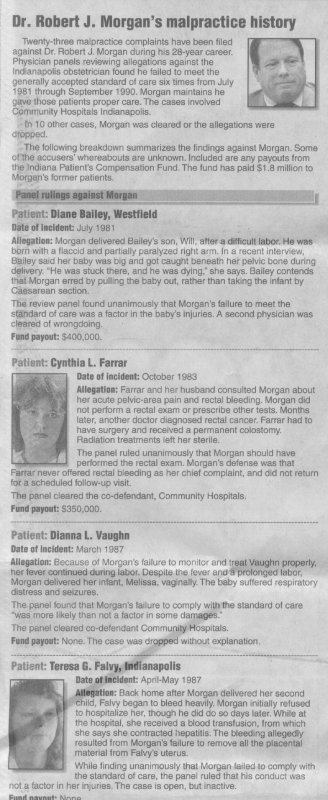

second day of the series led with the case of Cynthia

Farrar.

Farrar and her husband had obtained a malpractice

settlement against Morgan, who they said failed to

perform a routine rectal exam on her when she went to him

in 1983 with complaints of rectal bleeding. Another

doctor later diagnosed cancer.

Cynthia Farrar had to have a permanent colostomy;

radiation treatments left her sterile.

Morgan earlier had lost another malpractice case, The

Star reported.

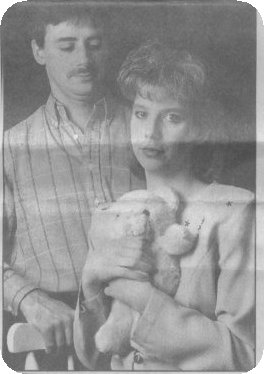

It was shocking news to Rebecca and Douglas Garvin.

A week earlier, they had buried their fourth child.

Going for a run

Rebecca Garvin's pregnancy defined high-risk. She had

lost twin sons to prematurity and a third child to

miscarriage.

Morgan, though not Garvin's regular physician, was on

call the night in April 1990 when she had pain.

Over the phone, Garvin related her tragic past and

symptoms. She recalls that Morgan seemed unconcerned and

prescribed no medication.

The next day - hemorrhaging - Garvin went to Community

East. There, Morgan examined her to determine whether she

was dilated. She wasn't. Garvin says he told her that she

was one of the reasons insurance rates were rising and

sent her home.

Another physician subsequently ordered a test to

determine the cause of the bleeding, then put Garvin on

bed rest. But two months later, Garvin, who had a history

of rapid labor, began having contractions.

Now in danger of giving birth just 22 weeks into her

pregnancy, Garvin asked for any physician but Morgan. But

again, only he was available.

Garvin says she was at the hospital at least three hours

before Morgan arrived.

This time, he ordered tests.

Then, Garvin says, Morgan announced that he was going for

a run. "I'll be back later," he said.

Morgan's casual attitude distressed Garvin and her

husband.

"We were fighting for our daughter's life,"

Rebecca Garvin said.

After returning, Morgan gave Garvin drugs to suppress her

contractions, then transferred her to another hospital.

But by then, Garvin had begun to dilate.

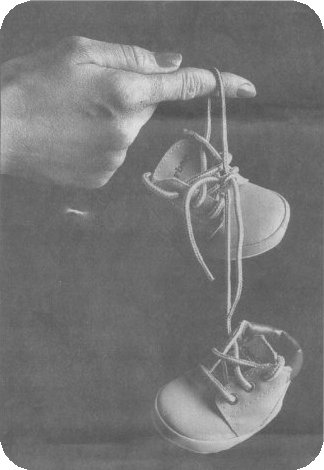

Dark-haired Nicole Linden Garvin, weighing a pound, died

in her parents' arms.

Morgan insists that he gave Garvin the "national

standard of care." But he acknowledges that while

awaiting an ultrasound, he did go for a stress-reducing

run.

"She was one of those cases who was just difficult.

. . . And I ran from the hospital and then ran back,"

he said. Morgan added dryly, "I could have sat in

the doctors' lounge."

The Garvins' baby was so premature that her chances of

survival were poor.

Could the pregnancy have been extended, and Nicole's

chances for survival improved, had Morgan taken her

mother's complaints more seriously?

The Garvins admit they don't know.

But at least, Douglas Garvin said, she would have had

"a fighting chance."

A mother's questions

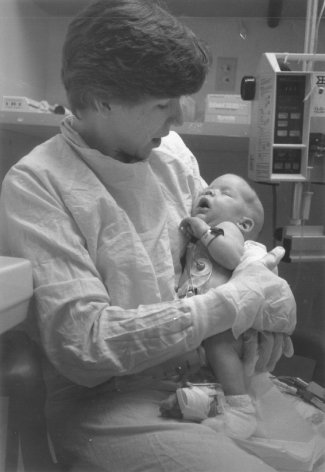

Myrna Hurless says Morgan didn't take seriously her

complaints of bleeding, either.

During her troubled 1993 pregnancy, Morgan allegedly told

the 17-year-old mother of one that she was too young to

have two kids anyway. Another time, the waitress asked

Morgan whether she should be on bed rest. "No,"

Hurless says Morgan replied. "You'll get fat and

lazy."

Hurless delivered an 11-ounce son, 3 1/2 months early.

The infant lived 48 minutes.

Morgan, who was not present for the delivery, denies poor

prenatal care and says he never made snide comments to

Hurless. Distraught people, he observes, sometimes get

such "things" in their heads.

But in her complaint to the state, Hurless blamed Morgan

for her devastated life.

"Now my son was dead," she wrote, "and I

had a doctor who didn't care."

A

doctor's defense:

To Robert Morgan, all this talk about individual cases

misses the larger point: On average, he says, his

patients have faired better than those of other local

physicians. And, he added, his number of "surgical

interventions" was the lowest around.

"You're looking at little bitty case incidents that

are major to these people," Morgan told a reporter.

"Where you're losing sight is that medicine needs to

change. It needs to reduce costs. (And) it needs to keep

good outcomes."

Morgan says he has delivered more than 3,000 babies, but

that critics unfairly dwell on a relatively few bad

results.

Among medical specialties, obstetrics-gynecology ranks

high for the number of malpractice claims. Nationally,

almost three-quarters of obstetrician-gynecologists have

been accused of negligence at least once; nearly a

quarter have had four claims or more.

Of the 33 malpractice claims filed against Morgan, 10

have been dropped or resolved in his favor.

In other cases, Morgan says, he agreed to settle

malpractice complaints rather than point an incriminating

finger at co-defendants.

Morgan also says that in an act of conscience, he once

warned his patients about a clip he had used in surgeries

that he later determined was faulty. When some patients

turned around and sued him, his malpractice insurer

refused to renew his coverage, he says.

Morgan's next insurer also refused to renew. Again, the

physician says, it was related to his malpractice claims.

Morgan feels picked on by Community Hospitals, too.

He says officials, for example, questioned why he didn't

call a resuscitation team more often. And Community urged

him to be more generous in dispensing epidurals to

laboring women in pain.

But Morgan says he felt better able than most to care for

distressed newborns.

And he maintains that it should be the doctor's call -

not the woman's - whether medications are used.

Epidurals, he says, can interfere with labor, adding that

he needs the patient's cooperation to push. "I can't

have her paralyzed," he says.

Morgan is derisive about "defensive medicine" -

doing procedures partly to guard against negligent

complaints.

"One of the real problems has been that doctors have

to worry about being sued, and . . . I tend not to

practice that way," he said in his state deposition.

"Unfortunately, I'm being reviewed by people who

practice that way, and I'm being critiqued by a hospital

which is very sensitive to adverse publicity."

Morgan says he was even told, "You can't be

different."

Dollars

and deference:

Yet through it all - rising malpractice claims, nurses'

incident reports, internal hospital scrutiny - Morgan

kept working.

And Community Hospitals continued to market him.

Until 3 1/2 years ago, when the hospitals removed him

from the service, Morgan remained on Community's

telephone physician-referral line.

To Lori Rollins' malpractice attorney, Bruce Kehoe, the

reason for Community's deference toward Morgan is clear.

"It's money," he said. "Deliveries going

through the door."

Morgan boasts that he once had "by far" the

largest obstetrical practice in Marion County. And he

says he brought in up to 300 deliveries per year for

Community.

He says he was for years Community's top-producing

obstetrician, "if you want to look at medicine in

those terms, and I assure you that hospitals do."

But Morgan says the hospitals soured on him when

patients' complaints appeared in news stories.

Community Hospitals rejects suggestions that either fear

of bad publicity or Morgan's big practice affected its

actions toward the physician. A doctor's qualifications

to be on staff are judged by panels of other private

physicians who do not benefit from the success of that

doctor's practice, the hospitals say.

And while not disputing Morgan's contention that he was a

high-volume obstetrician, the hospitals add: "This

was many years in the past."

The

scrutiny grows:

Morgan's practice began to unravel in 1995.

Care that he rendered to three patients would trigger

more malpractice claims. And there were additional

incidents, publicly revealed for the first time in the

attorney general's complaint.

Morgan, the complaint said, failed to properly

resuscitate or treat three struggling newborns.

In December 1995, Community East took action to deny

renewal of Morgan's obstetrical privileges and ordered

him to undergo a physician-assessment program in Colorado.

But months later, Community reappointed him with

conditions.

Morgan had to obtain a physician adviser to discuss his

cases, and rectify deficiencies in his patient charts.

Community also ordered Morgan evaluated for disruptive

behavior.

Morgan reduced some of his pregnant patients to tears

when he scolded them about weight gain or did not answer

their questions. His demanding manner also intimidated

some nurses.

One former patient who sued Morgan for malpractice,

Kimberly Cole, says her nurses at Community East seemed

"scared to death of him."

Some made unsettling comments about Morgan.

"Listen," one nurse told Cole and her husband,

"you don't know this doctor."

Particularly concerning to some nurses was Morgan's habit

of laying newborns on their mothers' abdomens after

delivery. Morgan says the technique warms the babies and

bonds them with their mothers.

He contends that concerns arose when nurses at Community

North jumped to the wrong conclusion that some

unresponsive babies needed urgent treatment.

Morgan says newborns sometimes look worse than they are.

They don't need resuscitation, he says, just a bit of

stimulation. After that, he says, it is perfectly safe to

give the baby to Mom.

Morgan rejects the "disruptive" charge as a

"tag" that a Community Hospitals administrator

hung on him.

And he asks sardonically how he could have had such a

large, thriving practice if everyone hated him.

Morgan

certainly has defenders:

Beth Bowles of Indianapolis credits the physician's quick

action with saving her oldest child's life. Her son Chris

was born with a hole in his lung and could not breathe.

So Morgan "immediately went to work on the baby,"

Bowles said. Chris today is a normal, healthy 9-year-old.

Nancie Hicks of Cumberland recalls how Morgan, as she was

going under anesthetic for a surgery, held her hand and

comforted her.

And Elizabeth Abbott of Indianapolis recounts how during

one hospital attempt at labor, Morgan let her remove a

scratchy fetal monitor strip from her abdomen so she

could sleep.

Abbott calls it a "shame" that such a caring

doctor isn't still delivering babies.

Community Hospitals officials privately judged Morgan's

clinical skills "of acceptable quality." They

concluded that some of the malpractice claims and other

complaints may arise from "Dr. Morgan's aggressive,

self-proclaimed `ahead of his time' and nonconventional

approach to the practice of medicine."

Also: "Dr. Morgan's narcissistic and defensive

personality, and his poor documentation of (patient)

histories" might explain the large number of

complaints.

In April 1996, Community Hospitals officials had one more

worry.

They fretted about whether Morgan's medical judgment was

clouded by his "strong desire to minimize the number

of C-sections that he performs." |